Leadership and Humanitarian Training for Leaders

17 Septembre 2018

Initiating and managing community projects is a difficult task. In many cases this work is undertaken by locally" based management groups. Such groups may be responsible for the operation of projects working with women. So far, they will need a hep and assistance from someone who will assist them in achieving goals.

Often these projects involve the employment of several staff and the provision of broad ranging educational and developmental programmers. Being responsible for this kind of work is, for any group, demanding job. It is particularly so for groups in disadvantaged areas where skills, experience and resources to undertake this kind of work are limited. In addition to this, those managing such projects are often struggling in their own lives to make ends meet.

The aim of this overview is to indicate some of key ways to assist local communities to manage their projects. It does this by looking at what is meant by community development, by presenting the role of the community development practitioner through the 4 phases of project cycle. The part one emphasizes the phases of project cycle. These are:

The part two empathizes, the risk management. The manger should identify the sources of risk. This should be done by exploring potential risk on a project. Some examples of categories for potential risks include the following:

PART 1: LEADERSHIP THROUGH PROJECT AND RISK MANAGEMENT

Community development as a term has taken off widely in anglophone countries i.e. the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Canada and New Zealand and other countries in the Commonwealth of Nations. It is also used in some countries in Eastern Europe with active community development associations in Hungary and Romania. The Community Development Journal, published by Oxford University Press, since 1966 has aimed to be the major forum for research and dissemination of international community development theory and practice ([1]).

Community Development Exchange defines community development as: both an occupation (such as a community development worker in a local authority) and a way of working with communities. Its key purpose is to build communities based on justice, equality and mutual respect.

Community development involves changing the relationships between ordinary people and people in positions of power, so that everyone can take part in the issues that affect their lives. It starts from the principle that within any community there is a wealth of knowledge and experience which, if used in creative ways, can be channeled into collective action to achieve the communities' desired goals.

Community development practitioners work alongside people in communities to help build relationships with key people and organizations and to identify common concerns. They create opportunities for the community to learn new skills and, by enabling people to act together, community development practitioners help to foster social inclusion and equality ([2]).

Many authors developed theories about types of community projects. Here we will base our explanation on the types as described by David B. Ryan [3] based on his experience[4]. For David B., some projects can have concrete results, such as helping community members to improve educational skills or providing goods and services directly to local families who may not qualify for state or federal assistance programs.

[1] Community Development Journal- about the journal". Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

[2] http://cdx.org.uk/community

[3] ) https://bizfluent.com/types-community-projects-10211.html

[4]) David B. Ryan has been a professional writer since 1989. His work includes various books, articles for "The Plain Dealer" in Cleveland and essays for Oxford University Press. Ryan holds degrees from the University of Cincinnati and Indiana University and certifications in emergency management and health disaster response.

2. Examples of Types of community projects

Many authors developed theories about types of community projects. Here we will base our explanation on the types as described by David B. Ryan [1] based on his experience[2]. For David B., some projects can have concrete results, such as helping community members to improve educational skills or providing goods and services directly to local families who may not qualify for state or federal assistance programs.

2.1. Food-Related Projects

This type of project can involve the poor and the elderly who may have money but lack transportation to stores. It offers communities a focus for volunteer projects such as: community food banks, food cooperatives and programs, such as the Meals on Wheels Association of America, use volunteers to provide meals to seniors and shut-ins. Food programs may also involve animal care. Community outreach programs, sometimes associated with senior centers, provide a chance for volunteers to deliver pet food directly to the pet owner, when transportation is unavailable to the pet caregiver. Neighborhood programs at local churches, branches of the Salvation Army, and outreach programs that feed the poor at local cafeterias also use volunteers.

2.2. Tutoring & Education Projects

Tutoring and education provide the focus areas for other community projects. A program might help at schools during lunch or snack time or assist the school librarian or computer-room technician. Community assistance projects also provide subject-area tutoring or mentor volunteering for young children without a parent to influence them. Local branches of Big Brothers and Sisters provide mentoring services in communities. Local library programs assist in reading programs or helping to re-shelve books. Community library volunteers may also tutor after school at library branches. Adult volunteers with computer skills may be organized into groups to volunteer at local schools to train students in one-on-one programs to learn to research using the Internet. Community health and fitness programs also work at schools to improve children's diet choices, encourage formal exercise and provide supervision for students to exercise at recess time or in after-school sports and recreation activities.

2.3. Safety Projects

Community safety projects work to assist local law enforcement, fire fighters or the community Federal Emergency Management Agency in efforts to coordinate branches of the Community Emergency Response Teams. These groups help prepare the community for natural disasters, including floods or extreme summer or winter temperatures, and respond in actual disasters. Other community safety projects include working as a coordinator for the Red Cross or American Heart Association to train community members in first aid, CPR or the use of defibrillators.

2.4. Beautification Projects

Beautification projects provide a focused community effort to complete a single project in a specified period. You might paint park structures and bandstands, plant and weed public gardens and beautify road medians—all projects that use many volunteers in a concentrated effort focusing on a single goal. The Arbor Day Foundation helps communities organize projects around the April day that focuses on planting trees. Other community groups, including Key Club International programs at local schools, develop projects to help with neighborhood improvement. These groups organize paint and cleaning projects for seniors unable to care for residences.

[1] ) https://bizfluent.com/types-community-projects-10211.html

[2]) David B. Ryan has been a professional writer since 1989. His work includes various books, articles for "The Plain Dealer" in Cleveland and essays for Oxford University Press. Ryan holds degrees from the University of Cincinnati and Indiana University and certifications in emergency management and health disaster response.

3. Importance of Community centers

In villages there are various community centers that look after various aspects of life of the village people. These community centers perform the following functions:

1) Establishing reading rooms and libraries and encouraging people to come over there.

2) Encouraging the village people to improve their standards of living. They arrange films and take to other programs in this respect.

3) Take to various cultural programs.

4) They can establish contact with the guardians of the schools and arrange student guardians meet.

5) They can establish bodies and organizations for the welfare of the boys and girls.

6) They can undertake program of National and Emotional Integration and observe National Festivals in a manner that nationalism is strengthened.

Such centers have been envisaged in the program for community development but so far these centers have not started functioning in the desired manner and direction.

4. The 4 Phases of the Project Management Life Cycle

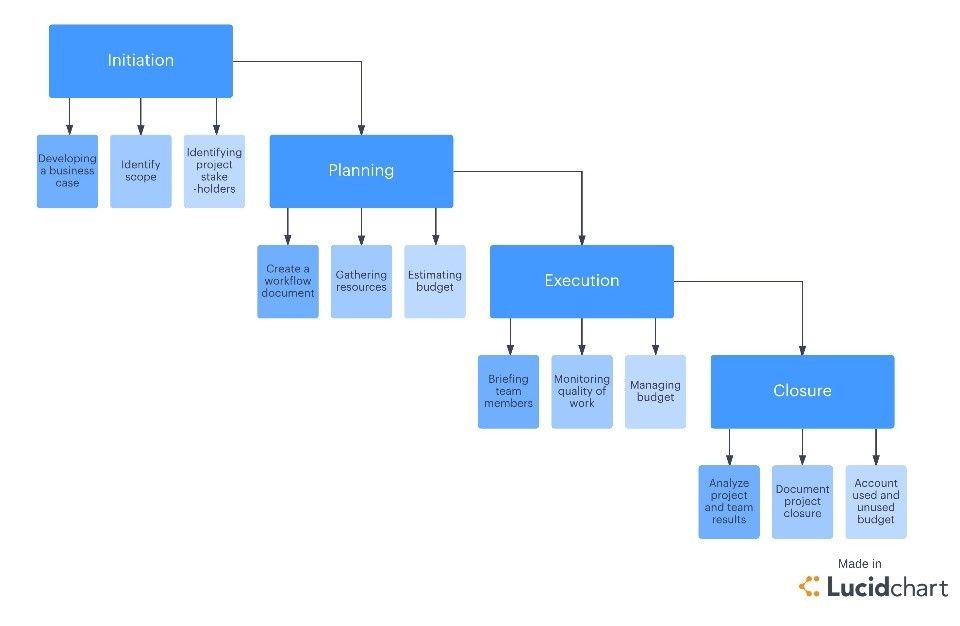

The project management life cycle is usually broken down into four phases: initiation, planning, execution, and closure—these make up the path that takes your project from the beginning to the end.

Some methodologies also include a fifth phase, controlling or monitoring. For our purposes, this phase is covered under the execution and closure phases.

Source: Project Management Life Cycle as presented by Lucidchart

4.1. The Initiation Phase

During the initiation phase of the project, the expert and communities should identify a business need, problem, or opportunity and brainstorm ways that your team can meet this need, solve this problem, or seize this opportunity. During this step, they should figure out an objective for the project, determine whether the project is feasible, and identify the major deliverables for the project.

Instead of waiting to have the project strategy decided, Moira Alexander advocates for a mental switch from being a project "manager" to becoming a project "leader":

"Project managers must be able to sell business leaders on the intrinsic value they offer to the business at a strategic level when they are at the table from the start of strategic planning instead of after the fact decision-making. Project managers effectiveness is drastically muted when offering a "fix-it" or "workaround" once high-level directional business decisions are made without their expertise."

Clearly, it's worth it to do what it takes to make your voice heard early, before the strategy is set in stone.

Project management steps for the initiation phase

Steps for the project initiation phase may include the following:

The expert and communities should also develop a statement of work or project initiation document, which may include basic project life cycle flowcharts.

4.2. Planning

Once the project is approved to move forward based on your business case, statement of work, or project initiation document, you move into the planning phase. In this phase, you break down the larger project into smaller tasks, build your team, and prepare a schedule for the completion of assignments. During this phase, you create smaller goals within the larger project, making sure each is achievable within the time frame. Smaller goals should have a high potential for success.

Step-by-step planning is necessary for each activity in a group programmed of work. Answering the following questions should help a group plan every activity, whether big or small, clearly and effectively.

Participative planning may not be very easy. For example, bringing together the management committee, staff and participants of a project to plan a year's programmed could be difficult. A way of doing this could be to ask each group to take time on their own to plan and then to bring representatives of each group together to work out a final plan. An outside facilitator may be helpful in this process

Planning involves asking and answering:

(a) What are we aiming to do?

(b) How do we aim to do it?

(c) Who will be responsible for seeing that it

is done?

(d) How will we measure how well we have

done it?

Plans must be recorded and, after specific time, evaluated. Plans should be realistic and achievable, and they must be put into action.

Finally, the plans that are made must be put into action. It is frustrating and disillusioning for a group that has put time and effort into plans to see them ignored or forgotten. This is also why keeping written record of plans, which can be regularly referred to, is so

Important.

Steps for the project planning phase may include the following:

The planning phase is also where you bring your team on board, usually with a project kickoff meeting. It is important to have everything outlined and explained so that team members can quickly get to work in the next phase.

4.3. Execution

When you have received business approval, developed a plan, and built your team. Now it’s time to get to work. The execution phase turns your plan into action. The project manager’s job in this phase of the project management life cycle is to keep work on track, organize team members, manage timelines, and make sure the work is done according to the original plan.

Steps for the project execution phase may include the following:

4.4. Closure

Once your team has completed work on a project, you enter the closure phase. In the closure phase, you provide final deliverables, release project resources, and determine the success of the project. Just because the major project work is over, that doesn’t mean the project manager’s job is done—there are still important things to do, including evaluating what did and did not work with the project.

Steps for the project closure phase may include the following:

PART 2: LEADERSHIP THROUGH RISK MANAGEMENT FOR LOCAL PROJECTS

After explaining how the manger should guide and assist the communities in managing the four phases of the project (part 1), the second part focus on how to manage risks while managing the project. In this paper we will have to explain [1]:

Managing risks on projects is a process that includes risk assessment and a mitigation strategy for those risks. Risk assessment includes both the identification of potential risk and the evaluation of the potential impact of the risk. A risk mitigation plan is designed to eliminate or minimize the impact of the risk events—occurrences that have a negative impact on the project. Identifying risk is both a creative and a disciplined process. The creative process includes brainstorming sessions where the team is asked to create a list of everything that could go wrong. All ideas are welcome at this stage with the evaluation of the ideas coming later

[1] https://pm4id.org/chapter/11-2-risk-management-process/

1.1. Risk Identification

In this first step of the risk management process, you and your project team identify as many potential risks, events, factors, and other items that threaten the success of your project. These are threats to the scope, quality, schedule, budget, personnel, procurements, and other things of importance. The goal of the first pass through this Identify Risks step is to create a master list of all potential risks to the project.[1]

Multiple methods can be used to identify these risks, including team brainstorming, systematic methodologies, and examining what happened on other similar projects. It’s also often useful to seek the counsel of outside experts and other PMs who have managed similar projects to yours.

Risks identified should include programmatic, technical, external, corporate, and other types. I.e., these are not just one type, such as technical. Instead, the goal is to find all types of risks that threaten your project in any manner. Don’t worry about whether a potential risk is too small or unlikely to occur at this point; just write everything down.

Risks that are like each other are sometimes rolled up into single combined risks. High-level categories are then used to group individual identified risks together into broader logical areas. Frequently, these categories align with the higher-level PBS or WBS areas of the project, but they may include other categories, too, such as stakeholders and general procurements.

The first time you perform this step should result in the creation of a preliminary risk register that contains all identified risks. Often this is created in a spreadsheet format. In future passes through the process cycle, new risks are identified during this repeated step, and are added to the risk register.

A more disciplined process involves using checklists of potential risks and evaluating the likelihood that those events might happen on the project. Some companies and industries develop risk checklists based on experience from past projects. These checklists can be helpful to the project manager and project team in identifying both specific risks on the checklist and expanding the thinking of the team. The experience of the project team, project experience within the company, and experts in the industry can be valuable resources for identifying potential risk on a project.

Identifying the sources of risk by category is another method for exploring potential risk on a project. Some examples of categories for potential risks include the following:

The people category can be subdivided into risks associated with the people. Examples of people risks include the risk of not finding the skills needed to execute the project or the sudden unavailability of key people on the project. David Hillson1 uses the same framework as the work breakdown structure (WBS) for developing a risk breakdown structure (RBS). A risk breakdown structure organizes the risks that have been identified into categories using a table with increasing levels of detail to the right.

In John’s move, John makes a list of things that might go wrong with his project and uses his work breakdown structure as a guide. A partial list for the planning portion of the RBS is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Risk Breakdown Structure (RBS)

The result is a clearer understanding of where risks are most concentrated. Hillson’s approach helps the project team identify known risks but can be restrictive and less creative in identifying unknown risks and risks not easily found inside the work breakdown structure

[1] http://www.theprojectmanagementblueprint.com/?p=277

1.2. Risk Evaluation (Analyze & Prioritize Risks)

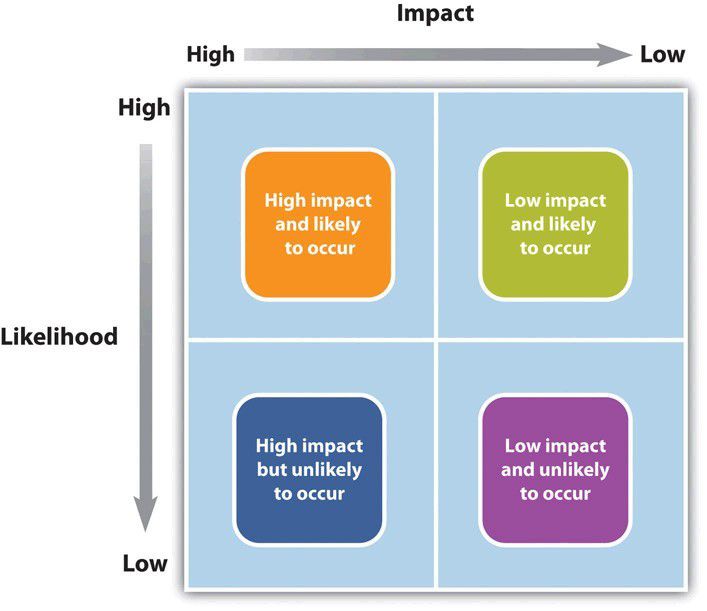

After the potential risks have been identified, the project team then evaluates the risk based on the probability that the risk event will occur and the potential loss associated with the event. Not all risks are equal. Some risk events are more likely to happen than others, and the cost of a risk event can vary greatly. Evaluating the risk for probability of occurrence and the severity or the potential loss to the project is the next step in the risk management process.

In this second step of the risk management process, an analysis of each identified risk from the previous step is performed by you and your team. This is done in two parts. The first analysis performed is qualitative in nature and helps create an initial gut-level sorting or “triaging” of the list into a prioritized ranking. Then a more formal quantitative analysis is performed on the identified risks, starting with the higher priority risks, and then working down through the list.

A qualitative likelihood (i.e., probability) of each identified risk is estimated, such as “unlikely,” “moderately likely,” or “highly likely” to occur. This is a subjective analysis to initially just categorize each risk.

A qualitative assessment of the impact of each risk is also performed. This is essentially the “damage” that will result if the risk is triggered and becomes an actual issue. Typically, three subjective categories are used to categorize the impact of a risk, such as “minor impact,” “moderate impact,” or “major impact” impact.

The initial qualitative assessment of likelihood and impact are then plotted on a risk assessment matrix, which helps determine the overall “seriousness” of each identified risk. This step helps focus your attention on the more important risks that threaten your project, and not waste time or effort analyzing less important risks. For example, a risk that has a high probability of occurring, but a very low impact, probably has an overall lower seriousness than a risk with a medium probability risk and high impact.

Having criteria to determine high impact risks can help narrow the focus on a few critical risks that require mitigation. For example, suppose high-impact risks are those that could increase the project costs by 5% of the conceptual budget or 2% of the detailed budget. Only a few potential risk events met these criteria. These are the critical few potential risk events that the project management team should focus on when developing a project risk mitigation or management plan. Risk evaluation is about developing an understanding of which potential risks have the greatest possibility of occurring and can have the greatest negative impact on the project. These become the critical few.

Figure 2. Risk and Impact

There is a positive correlation—both increase or decrease together—between project risk and project complexity. A project with new and emerging technology will have a high-complexity rating and a correspondingly high risk. The project management team will assign the appropriate resources to the technology managers to assure the accomplishment of project goals. The more complex the technology, the more resources the technology manager typically needs to meet project goals, and each of those resources could face unexpected problems.

Risk evaluation often occurs in a workshop setting. Building on the identification of the risks, each risk event is analyzed to determine the likelihood of occurring and the potential cost if it did occur. The likelihood and impact are both rated as high, medium, or low. A risk mitigation plan addresses the items that have high ratings on both factors—likelihood and impact.

1.3. Risk Analysis of Equipment Delivery

A project team analyzed the risk of some important equipment not arriving to the project on time. The team identified three pieces of equipment that were critical to the project and would significantly increase the costs of the project if they were late in arriving. One of the vendors, who was selected to deliver an important piece of equipment, had a history of being late on other projects. The vendor was good and often took on more work than it could deliver on time. This risk event (the identified equipment arriving late) was rated as high likelihood with a high impact. The other two pieces of equipment were potentially a high impact on the project but with a low probability of occurring.

Not all project managers conduct a formal risk assessment on the project. One reason, as found by David Parker and Alison Mobey2 in their phenomenological study of project managers, was a low understanding of the tools and benefits of a structured analysis of project risks. The lack of formal risk management tools was also seen as a barrier to implementing a risk management program. Additionally, the project manager’s personality and management style play into risk preparation levels. Some project managers are more proactive and will develop elaborate risk management programs for their projects. Other managers are reactive and are more confident in their ability to handle unexpected events when they occur. Yet others are risk averse, and prefer to be optimistic and not consider risks or avoid taking risks whenever possible.

On projects with a low complexity profile, the project manager may informally track items that may be considered risk items. On more complex projects, the project management team may develop a list of items perceived to be higher risk and track them during project reviews. On projects with greater complexity, the process for evaluating risk is more formal with a risk assessment meeting or series of meetings during the life of the project to assess risks at different phases of the project. On highly complex projects, an outside expert may be included in the risk assessment process, and the risk assessment plan may take a more prominent place in the project execution plan.

On complex projects, statistical models are sometimes used to evaluate risk because there are too many different possible combinations of risks to calculate them one at a time. One example of the statistical model used on projects is the Monte Carlo simulation, which simulates a possible range of outcomes by trying many different combinations of risks based on their likelihood. The output from a Monte Carlo simulation provides the project team with the probability of an event occurring within a range and for combinations of events. For example, the typical output from a Monte Carlo simulation may reflect that there is a 10% chance that one of the three important pieces of equipment will be late and that the weather will also be unusually bad after the equipment arrives.

1.4. Risk Mitigation Plan Risk Responses

After the risk has been identified and evaluated, the project team develops a risk mitigation plan, which is a plan to reduce the impact of an unexpected event. The project team mitigates risks in the following ways:

In this step, responses are developed for the various risks in the risk register. These responses are essentially the individual plan or plans that you and your team will implement to minimize the likelihood and/or impact of each significant risk. The threshold for developing formal responses is usually determined by way of the seriousness ranking of the individual risks.

For risks above a specific threshold, formal risk responses are developed by the project team. These responses usually employ one or more standard techniques, such as avoidance, mitigation, risk transfers (e.g., buying insurance), or just acceptance and monitoring of the risk.

There can be more than one response plan identified for each single risk. These responses might be applied in parallel or serve as backups to one another.

At this point, contingency reserve budgets are also often created (or at least informed) from the expected cost estimates in the risk register. Some projects use the risk register as a type of list of liens against the contingency budget to help ensure that adequate funds are available to address the more serious and/or costly risks.

All risk responses are included in the risk register.

Each of these mitigation techniques can be an effective tool in reducing individual risks and the risk profile of the project. The risk mitigation plan captures the risk mitigation approach for each identified risk event and the actions the project management team will take to reduce or eliminate the risk.

2. Contingency Plan

The project risk plan balances the investment of the mitigation against the benefit for the project. The project team often develops an alternative method for accomplishing a project goal when a risk event has been identified that may frustrate the accomplishment of that goal. These plans are called contingency plans. The risk of a truck drivers’ strike may be mitigated with a contingency plan that uses a train to transport the needed equipment for the project. If a critical piece of equipment is late, the impact on the schedule can be mitigated by making changes to the schedule to accommodate a late equipment delivery.

Contingency funds are funds set aside by the project team to address unforeseen events that cause the project costs to increase. Projects with a high-risk profile will typically have a large contingency budget. Although the amount of contingency allocated in the project budget is a function of the risks identified in the risk analysis process, contingency is typically managed as one-line item in the project budget.

Some project managers allocate the contingency budget to the items in the budget that have high risk rather than developing one-line item in the budget for contingencies. This approach allows the project team to track the use of contingency against the risk plan. This approach also allocates the responsibility to manage the risk budget to the managers responsible for those line items. The availability of contingency funds in the line item budget may also increase the use of contingency funds to solve problems rather than finding alternative, less costly solutions. Most project managers, especially on more complex projects, will manage contingency funds at the project level, with approval of the project manager required before contingency funds can be used.

3. Communicate with Stakeholders

A primary role of Project Management is communicating to key stakeholders the status of project risks, their collective cost/schedule/quality/scope exposure, response plans, and the resolution of issues as they arise. As the project progresses, the communication step includes a description of changes and the addition and subtraction of new risks to the register.

4. Conclusion

The project has four phases. project cycle. These are: i) Initiation, ii) Planning; iii) Execution and iv) Closure. All the phases should be done jointly with the community through various bodies and local structures with participation of women. During the initiation phase of the project, the expert and communities should identify a business need, problem, or opportunity and brainstorm ways that your team can meet this need, solve this problem, or seize this opportunity. Planning is an essential part of community development work, both at the beginning and on an on-going basis. Planning should be participative and well organized. The execution phase turns your plan into action. The project manager’s job in this phase of the project management life cycle is to keep work on track, organize team members, manage timelines, and make sure the work is done according to the original plan. In the closure phase, you provide final deliverables, release project resources, and determine the success of the project.

A key aspect of this Risk Management process is its continuous nature. Said another way, once the initial risk register is created and in place, your job as project manager is not over– in fact, it’s just beginning. The secret to risk management success is repeating the steps of the cycle on a regular cadence, adding new risks as they arise, retiring expired risks, and continuously updating the risk register and communicating its status to stakeholders. The goal is to stay ahead of risks, before they overtake you and your project. It’s vitally important that you identify, analyze & prioritize, and plan appropriate responses to project risks. Failing to do so is like an ostrich putting its head in the sand, hoping the dangers that threaten it pass by. Don’t be the ostrich project!

Key elements

Risk mitigation is the development and deployment of a plan to avoid, transfer, share, and reduce project risk. Contingency planning is the development of alternative plans to respond to the occurrence of a risk event

5. Sources & References